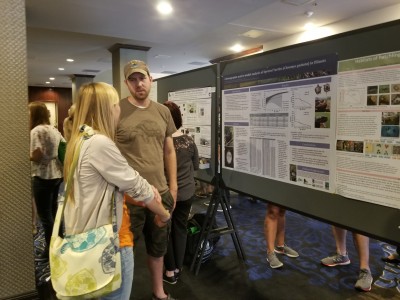

Sara Johnson, of the Molano-Flores lab at the Illinois Natural History Survey, presented a poster and lightning talk about Illinois Tollway funded research on the Effects of Soluble Salt on the Germination of Thuja occidentalis at the Great Lakes Coastal Wetlands Symposium in Maumee Bay, Ohio last week. This conference was the first symposium hosted by Audubon Great Lakes in partnership with the Great Lakes Coastal Assembly and Great Lakes Commission. Sara is a student representative for the North Central Chapter of the Society of Wetland Scientists and acts as Treasurer for the Student Chapter of the society at UIUC.

Sara Johnson, of the Molano-Flores lab at the Illinois Natural History Survey, presented a poster and lightning talk about Illinois Tollway funded research on the Effects of Soluble Salt on the Germination of Thuja occidentalis at the Great Lakes Coastal Wetlands Symposium in Maumee Bay, Ohio last week. This conference was the first symposium hosted by Audubon Great Lakes in partnership with the Great Lakes Coastal Assembly and Great Lakes Commission. Sara is a student representative for the North Central Chapter of the Society of Wetland Scientists and acts as Treasurer for the Student Chapter of the society at UIUC.

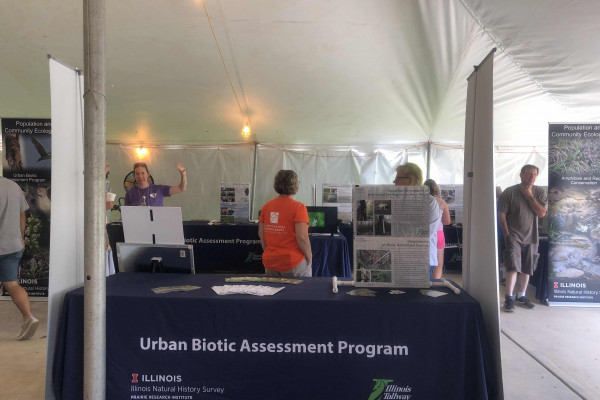

PaCE Lab at the Illinois State Fair

Members of the PaCE Lab exhibited in Conservation World at the 2019 Illinois State Fair, providing information and education to over 500 visitors. In addition to displays about the research being done by the group, visitors were able to try their hand at using actual field equipment used by scientists in their daily work.

The Illinois Bat Conservation Program had a mist net deployed where visitors could untangle, identify, and measure bats, all while wearing leather gloves.

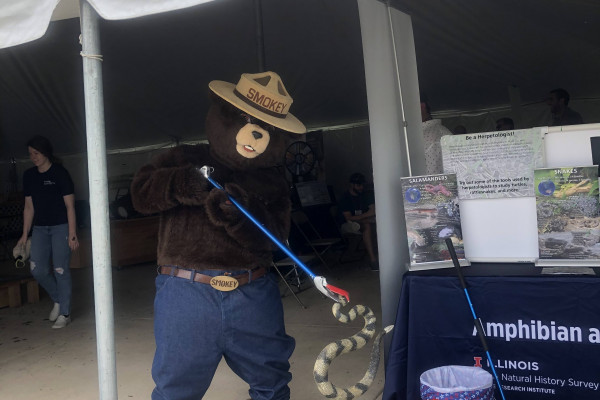

The Amphibian and Reptile Conservation group had snake tongs, hooks, calipers, and radio telemetry equipment available for visitors to try to wrangle snakes into a snake bag, measure turtles, or track a hidden turtle.

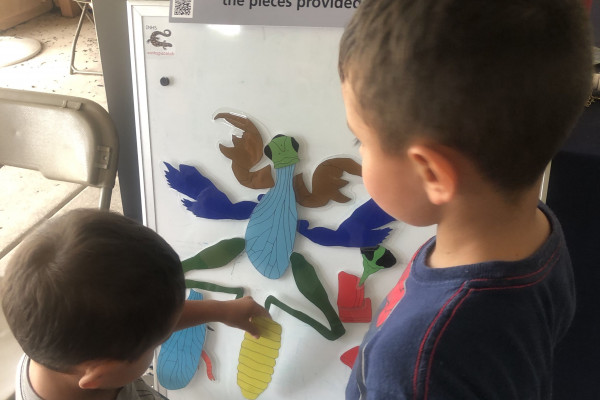

Other activities included Build-a-Bug, where people can assemble the arthropod of their dreams (or nightmares) from a variety of general and specialized appendages, Wheel of Migration, about the risks migratory birds face, and locating PIT-tagged animals.

New Publication on Spacial Ecology of Softshell Turtles

Read the complete article at https://www.mdpi.com/1424-2818/11/8/124:

A new paper by INHS PACE Lab herpetologists examined the movement of the state listed Smooth Softshell Turtle, Apalone mutica, a riverine species. Spatial ecological information is necessary to guide the conservation efforts of river turtles. Turtles were radio tracked and found to move on average 142 m per day, but moved more when water was high or streams were larger. In most situations, females moved greater distances than males. This work will guide future studies of riverine species.

UBAP Ornithologist Rahlin receives Kushlan Research Award

UBAP Ornithologist Anastasia Rahlin received the Kushlan Research Award from the Waterbird Society to assist her research project entitled “Using environmental DNA sampling to determine heron and bittern occupancy in western and northern Michigan: a metagenomics approach.”

This work will improve knowledge of the ranges and population sizes of Black-crowned Night Herons, Yellow-crowned Night Herons, American Bitterns, and Least Bitterns and will inform conservation and management decisions for these rare and declining wetland birds.

9 days, 3 conferences, 8 talks, 2 posters

It’s been a busy week of sharing science for members of the PACE lab.

The Chicago Wilderness Wildlife Committee Meeting was held at Lincoln Park Zoo on February 19th:

Tara Hohoff presented “The status of Illinois bats five years after confirmation of white-nose syndrome,” using data from her work with the Illinois Bat Conservation Program and the Urban Biotic Assessment Program monitoring for the Illinois Tollway.

Tara Hohoff presented “The status of Illinois bats five years after confirmation of white-nose syndrome,” using data from her work with the Illinois Bat Conservation Program and the Urban Biotic Assessment Program monitoring for the Illinois Tollway.

Joshua Sherwood presented “Assessing the distribution and habitat of Iowa Darters (Etheostoma exile) in Illinois,” with co-authors Andrew Stites, Jeremy Tiemann, and Michael Dreslik. This work changed the way people look for the Iowa Darter.

Joshua Sherwood presented “Assessing the distribution and habitat of Iowa Darters (Etheostoma exile) in Illinois,” with co-authors Andrew Stites, Jeremy Tiemann, and Michael Dreslik. This work changed the way people look for the Iowa Darter.

Jason Robinson presented “Patterns of abundance and co-occurrence of bumblebees associated with the Rusty Patched bumblebee.” RPBB is a federally protected species found in northeastern Illinois that has experienced a decline in its range.

Jason Robinson presented “Patterns of abundance and co-occurrence of bumblebees associated with the Rusty Patched bumblebee.” RPBB is a federally protected species found in northeastern Illinois that has experienced a decline in its range.

Jason Ross presented “Demographic influence of head-starting on a Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) population in DuPage County, Illinois,” with co-author Michael Dreslik, discussing what amount of head-starting is needed to keep this population viable

Jason Ross presented “Demographic influence of head-starting on a Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) population in DuPage County, Illinois,” with co-author Michael Dreslik, discussing what amount of head-starting is needed to keep this population viable

The 2019 Wild Things Conference was held in Rosemont on February 23rd:

Tara Hohoff, representing the Illinois Bat Conservation Program, presented a poster “Year Three of the Illinois Bat Conservation Program.”

Anastasia Rahlin co-presented “Secretive Marsh Birds in the Big City.” with Audubon collaborator Stephanie Beilke on their ongoing work using playback to detect 17 focal wetland bird species in northeast Illinois and southeast Indiana. Soras were the most commonly detected species which was surprising/unexpected since Marsh Wrens and Swamp Sparrows are expected to be more common, and Little Blue Herons and Yellow-headed Blackbirds were the least detected which was pretty expected due to their declines. Future directions include creating species-specific occupancy models to better understand how our focal species respond to urbanization and presence of different wetland types at three different spatial scales.

Josh Sherwood presented “Current status of Bigeye Chub (Hybopsis amblops) in Illinois”.

Sarah Douglass presented “A preliminary analysis of mussel population dynamics in the Kishwaukee River.”

Jeremy Tiemann presented “Pulling the plug – Results of the fish and mussel salvage following the removal of the Danville Dam on the Vermilion River.”

Andy Stites presented a poster “Fecundity estimates of the Gravel Chub Erimystax x-punctatus“

Edmonds receives grant to study Ornate Box Turtles

Congratulations to PACE Lab graduate student Devin Edmonds who received a grant from the Friends of Nachusa Grassland to study the hibernation patterns of the state threatened Ornate Box Turtle. This research will help inform land managers’ timing of prescribed burns to decrease risk of harm to this declining species.

Iowa Darter might not be as rare as believed

UBAP Ichthyologist Andrew Stites wrote a field account for the Illinois News Bureau’s Behind the Scenes to accompany a recent paper by Josh Sherwood, Andrew Stites, Michael Dreslik, and Jeremy Tiemann.

UBAP Ichthyologist Andrew Stites wrote a field account for the Illinois News Bureau’s Behind the Scenes to accompany a recent paper by Josh Sherwood, Andrew Stites, Michael Dreslik, and Jeremy Tiemann.

The paper, “Predicting the range of a regionally threatened, benthic fish using species distribution models and field surveys” developed a species distribution model for the state endangered Iowa Darter, after finding it in several new locations. This work was sponsored by the Illinois Tollway.

Read the Behind the Scenes: Finding darters where no one thought to look

Read the paper in The Journal of Fish Biology

Hourly Research Assistant needed

A technician is sought to collect demographic data on amphibians collected from drift fence arrays surrounding vernal wetlands in central Illinois and reptiles from cover board arrays in old field and prairie habitats in central and northern Illinois. The technician will work independently and with others to collect data on amphibian and reptile demographics (identify, count, weigh, mark, and measure species). Records data manually and electronically into a database using a tablet. Prepares, under supervision, data summaries and quarterly reports. The technician will be responsible for decontamination of sampling equipment and boots, maintenance of equipment and fences, data entry, data management, tissue collection, amphibian and reptile marking and operate a variety of hand tools, electronics, and mechanical equipment such as 4WD vehicles and Utility Terrain Vehicles.

Work is performed in prairie and wooded environments where there is exposure to extremes of weather and temperature. The work requires moderate to strenuous physical exertion such as long periods of standing, walking over rough, uneven, rocky, steep, and muddy surfaces; bending, crouching, stretching, lifting, and carrying up to 40 lbs. Long hours in the field should be expected and some work on weekends may be required. Duration of the season will be from mid-January through August 2019.

For more information and requirements see: https://blogs.illinois.edu/view/7426/717784

Graduate Research Assistanceship available in Amphibian Ecology and Conservation

M.S. Research Position in Amphibian Ecology and Conservation

Drs. Michael Dreslik (Illinois Natural History Survey) and John Crawford (National Great Rivers Research and Education Center) are seeking a graduate student to pursue a Master of Science with the Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences department at the University of Illinois (Urbana-Champaign). This is a funded project that will investigate the population ecology and demography of Jefferson-complex (Ambystoma jeffersonianum and A. platineum) and blue-spotted salamanders (A. laterale) in Illinois. Census techniques will include the use of drift fence arrays, minnow trapping, and dip-netting. There will be opportunities for the student to ask additional ecological questions within the study system. Additional research responsibilities will include: entering and analyzing data; presenting results at scientific meetings and writing scientific reports and manuscripts.

Competitive applicants will have: 1) a B.S. in Biology, Ecology, Wildlife or other related fields; 2) field research experience; 3) a strong work ethic; 4) ability to work well with others; and 5) a valid driver’s license. The successful applicant will be expected to enroll at the University of Illinois for the Spring 2019 semester (November 1 application deadline). Preference will be given to students with prior experience working with amphibians and/or drift fence arrays. To apply, combine cover letter, resume/CV, transcripts, GRE scores, and contact information (e-mail and phone) for three references into a single PDF document and submit by e-mail to Michael Dreslik (dreslik@illinois.edu) with the subject heading, “AmbystomaEcology”.

For more information, email Dr. Michael Dreslik (dreslik@illinois.edu) and/or Dr. John Crawford (joacrawford@lc.edu).

Strong showing from INHS PACE Lab at TSA

The #INHSPACELAB was well represented at the 2018 Turtle Survival Alliance Meetings in Fort Worth Texas, with 6 oral presentations and 3 posters.

Oral Presentations

Baker, S. J., E. J. Kessler, and M. E. Merchant. Antibacterial activities of plasma from the Common (Chelydra serpentina) and Alligator Snapping Turtle (Macrochelys temminckii).

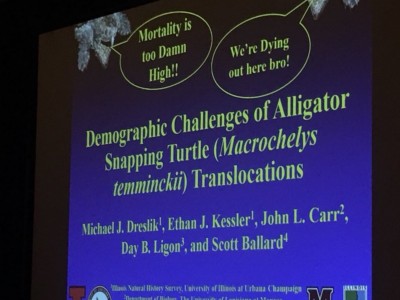

Dreslik, M. J., E. J. Kessler, J. L. Carr, D. B. Ligon, and S. Ballard. Mortality is too damn high: challenges of Alligator Snapping Turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) translocations.

Edmonds, D., R. Nyboer, and M. J. Dreslik. Population dynamics of the Ornate Box Turtle (Terrapene ornata) at two sites in Illinois.

Kessler, E. J., K. T. Ash, S. N. Barratt, E. R. Larson, and M. A. Davis. Assessing the efficacy of environmental DNA to detect Alligator Snapping Turtles (Macrochelys temminckii) at the edge of their range.

Merchant, M. E., E. J. Kessler, and S. J. Baker. Differences in innate immune mechanisms in Common and Alligator Snapping Turtles.

Ross, J. P., D. Thompson, and M. J. Dreslik. Demographic influence of head-starting on a Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii) population in DuPage County, Illinois.

Poster Presentation