Travel around Illinois in the spring and you are likely to see fields on fire. Many of these are intentionally set to aid land managers in reaching ecological goals. Prescribed burns can remove woody vegetation from prairies, remove invasive species, cycle nutrients back into the soil, and open up the canopy. These prescribed burns require much preparation and training.

Last week a group of staff from the Population and Community Ecology Lab (PACE lab) became certified to participate in prescribed burns.

Before being allowed to light our first fire, we had to complete online courses through the National Wildfire Coordinating Group to learn how to put out a wildfire. Through the courses – Human Factors in the Wildland Fire Service, Introduction to Wildland Fire Behavior, and Firefighter Training – we learned how to assess fire and weather conditions, control a fire, think critically in stressful situations, and survive when things go wrong.

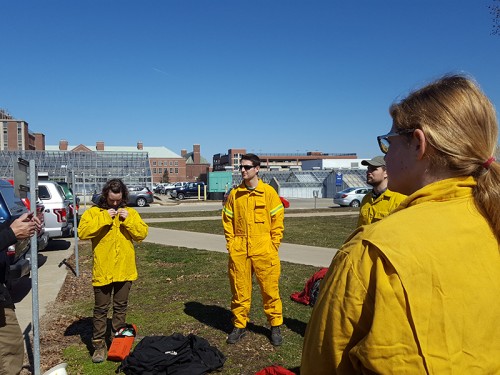

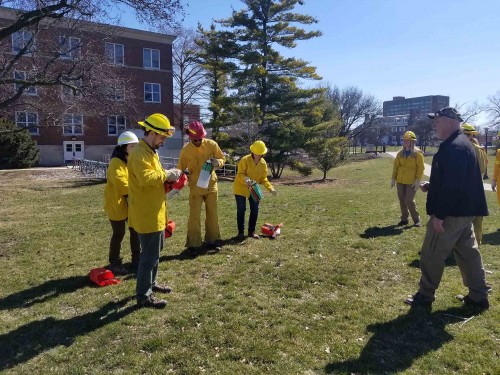

Our final day of coursework involved classroom activities, learning about different prescribed burn techniques, trying out personal protective equipment (PPE), practicing deployment of a fire shelter, and finally, starting a fire.

The U of I Committee on Natural Areas (CNA) had a small plot of land that needed to be burned north of campus. When we arrived, we found clear blue skies, light wind, and a piece of grassland bordered by woodlands full of singing Chorus Frogs to the north, privately owned bean fields to the east, and a long-term research project to the south. Jamie and Nate from the CNA had mowed down a 10ft wide swath of grass between the grassland and research plot. The woodland and bean field were separated from the prairie by a gravel and dirt path. This would be our control line.

Assessing the wind direction (from the NW), and the location of the surrounding areas we wanted to leave unburnt, we decided to start our backfire on the SE side of the prairie. By starting against the wind, we could slowly create a burned area bordering the remaining grassland creating an area that fire could not cross back over. If we started on the NW side, the wind would sweep the fire quickly across the entire field and likely into the areas we didn’t want to burn.

Wearing hardhats, goggles, and Nomex suits, we armed ourselves with backpack waterpumps, drip torches, fire rakes, fire flappers, and McLeods. We separated into two teams, one to burn the south side (Team 1) and one to burn the east side (Team 2). We quickly learned that things don’t always go as planned. Team 1’s drip torch wouldn’t drip, making it impossible to start fire. Team 2 had less trouble spreading fire and things got hot fast!

Once Team 2 got things going, it became clear that we needed to improve the southern control line, and all rakes and McLeods got to work trenching a line ahead of the drip torch. Those with flappers followed behind to snuff out spot fires and ensure any smoldering along the edges was put out.

As the fire engulfed more of the prairie, the flames and smoke intensified, the fire generated its own wind. Thick black smoke billowed above us and fire whirls spun flames and ash like tornadoes. When we reached the western edge of the grassland, we had burned a 20 foot wide strip in addition to the 10 foot control line between the rest of the grass and research plot. This tediously created area devoid of fuels would keep the fire from being able to jump to the research plot or the bean field, while the wind would keep the fire out of the woodland. We could now safely start a headfire that the wind could carry across the remaining grasses.

Once the area had been cleared, we walked the perimeter one last time to make sure there was no smoldering and nothing left behind. The only thing left unblackened were the bones of a deer that had been been picked clean by scavengers long before our fire.

Our final test was our After Action Review where we discussed what happened, what was good, what was bad, and what we learned.

For many, this was the first time that close to a fire and the heat and intensity was greater than anticipated, but all look forward to future opportunities to use this powerful tool.

photos by T Hohoff, M Dreslik, and J Mui