Herpetologist Dr. Sarah Baker presented at the Joint Meeting of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists in Syracuse NY. Her talk was titled: “Snake fungal disease reduces skin bacterial and fungal diversity in an endangered rattlesnake” (co-authors were Matt Allender, Megan Britton, and Angela Kent).

Rusty Patched Bumblebee

While conducting surveys today in DuPage County, INHS entomologist Jason Robinson and his assistant Maria Repisak came across Rusty Patched Bumblebees at two sites! This species was recently added to the US Endangered Species List because of its drastic decline across its range.

For more information on the Rusty Patched Bumblebee, visit the USFWS website

Photo by Maria Repisak

Snake Hydration Video Goes Viral

Herpetological Field Assistant Taylor West came across a Western Hognose Snake last week while surveying sand prairies. Given the hot temperatures, she and fellow field assistant Tristan Schramer offered the snake some water. Video of the encounter has been shared over 10,000 times!

Read more about the experience at Living Alongside Wildlife

Follow Taylor on Twitter @WildWildTWest

Herpetologist Christina Feng accepts position with IDNR

PACE Lab alumna Christina Feng has joined the Illinois Department of Natural Resources Natural Heritage Program as the District 7 Heritage Biologist. In this role she will continue to help protect and manage the natural resources of west-central Illinois. Feng received her M.S. from the U of I Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Sciences in winter 2017 for her work on Demography of the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) in Illinois.

INHS PACE Lab graduate student receives scholarship to study snakes

Grace Wu, is a master’s student with the Natural Resources and Environmental Science Department at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She has recently received a scholarship from The Garden Club of Downers Grove for her research in the field of wildlife conservation. Her thesis research topic is exploring the diversity, occupancy, and abundance of snake species within chronological stages of tallgrass prairie restoration. The study takes place within Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie located in Will County, Illinois. Along with a high-quality prairie remnant, Grant Creek Prairie Nature Preserve. The award will help purchase the 500 cover objects needed to survey snakes within Midewin and the IDNR site. Grace will be gathering data for three years, which will contribute to the understanding of little-known correlations between tallgrass prairie restoration and snake assemblages.

Searching for Turtles in a Sea of Grass

By Devin Edmonds

Historically the Ornate Box Turtle was known from 45 counties in Illinois. Today you can count the number of counties with confirmed populations on two hands. This decline landed the species on the List of Endangered and Threatened Species of Illinois in 2009, with habitat loss and road mortality being the greatest threats to its continued survival.

We had the opportunity to survey two of the largest known Ornate Box Turtle sites this past week, with the goal of finding, measuring, and marking as many turtles as possible. With enough recaptures, we can calculate how likely it is for an individual to survive from one year to the next and determine population size. This helps us answer questions including: has population size changed over time? Is the population stable, increasing, or decreasing? Is the population at risk of extinction?

Searching for reptiles and amphibians is often quite tedious. You have to carefully scan ahead of each step for movement before a snake gets away, or spend hours flipping over logs to find the particular salamander you are looking for.

Fortunately, we were assisted on our survey by John Rucker and his Boykin Spaniels, who are not pets but rather working dogs. Years ago one dog proudly brought John Rucker a box turtle it turned up in the woods of Tennessee. He praised the dog and soon it brought back another one in its mouth. Eventually he turned his group of turtle finding dogs into a profession, helping biologists find these once common but increasingly rare chelonians for study.

Fortunately, we were assisted on our survey by John Rucker and his Boykin Spaniels, who are not pets but rather working dogs. Years ago one dog proudly brought John Rucker a box turtle it turned up in the woods of Tennessee. He praised the dog and soon it brought back another one in its mouth. Eventually he turned his group of turtle finding dogs into a profession, helping biologists find these once common but increasingly rare chelonians for study.

With John’s dogs, our work was made easy. They carried on ahead of us, their noses to the ground, brown bodies nearly concealed by knee-high grass. When a turtle was found, a dog picked it up in its mouth and carried the reptile like a precious toy, walking to John with pride and eyeing anyone else who offered to take the turtle from it with suspicion. John praised the dog and then gave the turtle to one of us to to be worked up.

With John’s dogs, our work was made easy. They carried on ahead of us, their noses to the ground, brown bodies nearly concealed by knee-high grass. When a turtle was found, a dog picked it up in its mouth and carried the reptile like a precious toy, walking to John with pride and eyeing anyone else who offered to take the turtle from it with suspicion. John praised the dog and then gave the turtle to one of us to to be worked up.

To keep track of individual turtles we are catching and whether they survive from one year to the next we mark each turtle with a code. The process is called shell notching, and involves cutting little pieces out of the marginal scutes (the sections of shell that border the outer edge) to assign a unique identification code to each individual turtle. The scutes are numbered from one to twelve on left and right sides, and by notching different combinations of scutes on each side more than 30,000 individuals can be individually identified. For example, by cutting a little section of shell on the first scute on the left side and the third scute on the right, you have just identified an individual as 01L-03R. When done properly, the shell notches stay with the turtle for the rest of its life.

To keep track of individual turtles we are catching and whether they survive from one year to the next we mark each turtle with a code. The process is called shell notching, and involves cutting little pieces out of the marginal scutes (the sections of shell that border the outer edge) to assign a unique identification code to each individual turtle. The scutes are numbered from one to twelve on left and right sides, and by notching different combinations of scutes on each side more than 30,000 individuals can be individually identified. For example, by cutting a little section of shell on the first scute on the left side and the third scute on the right, you have just identified an individual as 01L-03R. When done properly, the shell notches stay with the turtle for the rest of its life.

Mortality events due to disease outbreaks have been documented in the closely related Eastern Box Turtle, and there is concern that the Ornate Box Turtle is also at risk. While we were marking and measuring turtles, Dr. Matt Allender and members of the Wildlife Epidemiology Lab were giving each turtle a physical exam, drawing blood, and swabbing their mouth and cloaca to screen for diseases and monitor health. Their work is providing a baseline for future studies on the health of box turtle populations.

With the help of the turtle dogs, we found more than one hundred turtles at the first site and nearly seventy at the second. The data is now awaiting entry and analysis, but several turtles we found were originally marked by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources in 1988. At more than 30 years of age, these individuals are approaching the maximum known lifespan for the species.

Together with the population health assessment, we expect our ongoing project will guide conservation efforts for the Ornate Box Turtle in Illinois and help ensure its continued survival.

Snakes in Central Illinois

PACE Lab leader Mike Dreslik was interviewed by the News Gazette to answer a reader’s question: “After reading the article about Snake Road in southern Illinois, I started wondering what species of snakes are found here in central Illinois? Have any new species been found over the last few years, with the milder winters?”

In addition to listing off species found in the area, Dreslik said, “Although it seems the winters are getting warmer, especially as spring approaches, we have not seen any new species of snakes moving into Illinois, we just see snakes emerging from their winter slumber sooner.”

Read the complete response at the News Gazette

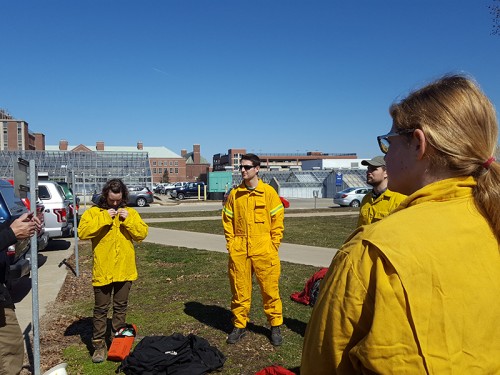

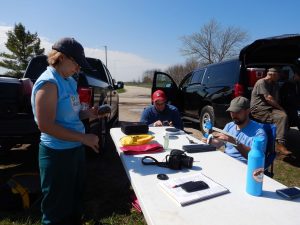

Licensed to burn

Travel around Illinois in the spring and you are likely to see fields on fire. Many of these are intentionally set to aid land managers in reaching ecological goals. Prescribed burns can remove woody vegetation from prairies, remove invasive species, cycle nutrients back into the soil, and open up the canopy. These prescribed burns require much preparation and training.

Last week a group of staff from the Population and Community Ecology Lab (PACE lab) became certified to participate in prescribed burns.

Before being allowed to light our first fire, we had to complete online courses through the National Wildfire Coordinating Group to learn how to put out a wildfire. Through the courses – Human Factors in the Wildland Fire Service, Introduction to Wildland Fire Behavior, and Firefighter Training – we learned how to assess fire and weather conditions, control a fire, think critically in stressful situations, and survive when things go wrong.

Our final day of coursework involved classroom activities, learning about different prescribed burn techniques, trying out personal protective equipment (PPE), practicing deployment of a fire shelter, and finally, starting a fire.

The U of I Committee on Natural Areas (CNA) had a small plot of land that needed to be burned north of campus. When we arrived, we found clear blue skies, light wind, and a piece of grassland bordered by woodlands full of singing Chorus Frogs to the north, privately owned bean fields to the east, and a long-term research project to the south. Jamie and Nate from the CNA had mowed down a 10ft wide swath of grass between the grassland and research plot. The woodland and bean field were separated from the prairie by a gravel and dirt path. This would be our control line.

Assessing the wind direction (from the NW), and the location of the surrounding areas we wanted to leave unburnt, we decided to start our backfire on the SE side of the prairie. By starting against the wind, we could slowly create a burned area bordering the remaining grassland creating an area that fire could not cross back over. If we started on the NW side, the wind would sweep the fire quickly across the entire field and likely into the areas we didn’t want to burn.

Wearing hardhats, goggles, and Nomex suits, we armed ourselves with backpack waterpumps, drip torches, fire rakes, fire flappers, and McLeods. We separated into two teams, one to burn the south side (Team 1) and one to burn the east side (Team 2). We quickly learned that things don’t always go as planned. Team 1’s drip torch wouldn’t drip, making it impossible to start fire. Team 2 had less trouble spreading fire and things got hot fast!

Once Team 2 got things going, it became clear that we needed to improve the southern control line, and all rakes and McLeods got to work trenching a line ahead of the drip torch. Those with flappers followed behind to snuff out spot fires and ensure any smoldering along the edges was put out.

As the fire engulfed more of the prairie, the flames and smoke intensified, the fire generated its own wind. Thick black smoke billowed above us and fire whirls spun flames and ash like tornadoes. When we reached the western edge of the grassland, we had burned a 20 foot wide strip in addition to the 10 foot control line between the rest of the grass and research plot. This tediously created area devoid of fuels would keep the fire from being able to jump to the research plot or the bean field, while the wind would keep the fire out of the woodland. We could now safely start a headfire that the wind could carry across the remaining grasses.

Once the area had been cleared, we walked the perimeter one last time to make sure there was no smoldering and nothing left behind. The only thing left unblackened were the bones of a deer that had been been picked clean by scavengers long before our fire.

Our final test was our After Action Review where we discussed what happened, what was good, what was bad, and what we learned.

For many, this was the first time that close to a fire and the heat and intensity was greater than anticipated, but all look forward to future opportunities to use this powerful tool.

photos by T Hohoff, M Dreslik, and J Mui

Rising temperatures could benefit the Snapping Turtle

Rising temperatures could benefit the Common Snapping Turtle.

CHAMPAIGN, ILL. — A recently published study of snapping turtle nests at Gimlet Lake in Garden County Nebraska from 1990 – 2015 found that warmer fall temperatures positively correlate to larger eggs and larger numbers of eggs, while warmer spring temperatures are negatively correlated with egg size and number.

Nesting females were observed and after depositing eggs, captured, measured, marked, and released. The nests were excavated and eggs were counted and measured before being reburied.

Maximum egg size is limited in many turtle species by the size of the female, specifically the pelvic aperture, thus surplus resources are used to develop a greater number of eggs rather than larger eggs. Although this limitation is present in many species of turtles, it was clear a different pattern existed within Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina). Large adult snapping turtles are not restricted in the size egg they can produce and in warmer years, produced larger eggs but the same number. Small adult snapping turtles, on the other hand, did not increase the size of their eggs, but produced larger clutches in warmer years.

Most temperate zone turtles begin developing their embryos in the fall, suspend development over the winter, and complete development in the spring. Snapping turtles complete the majority of their development in the fall, which may reduce the impact of winter and spring climate conditions.

Forming the eggs in the fall may enable snapping turtles to lay their eggs earlier and provide their young an advantage over other species. Herpetologist Michael Dreslik said,“Generalists like the Snapping Turtle tend to be more adaptable. The added benefit from warmer temperatures could allow Snapping Turtles to gather more resources for larger eggs or larger clutches.”

The mechanisms by which warmer temperatures influence egg and clutch size are unknown. Turtles are ectotherms, thus metabolism and physiology are impacted by environmental conditions.

“Warmer temperatures increase metabolism, but could result in greater food availability and more efficient processing of the food. Warmer temperatures could also affect the physiology of embryo development,” said lead author Ashley Hedrick. “Alternatively, in the spring, increased metabolism before food is readily available may require females to divert energy from egg development.”

While rising temperatures are generally considered problematic for most species, they could play in favor of the Snapping Turtle.

The paper “The Effects of Climate on Annual Variation in Reproductive Output in Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina).” is available online from the Canadian Journal of Zoology.

Corresponding author: J.B. Iverson email: johni@earlham.edu

To reach Ashley Hedrick, email arhedri11@gmail.com

To reach Michael Dreslik, email dreslik@illinois.edu

Photo by Jason P. Ross

Midwest Fish and Wildlife Meeting

UBAP herpetologist Sarah Baker co-organized a symposium “Advances and Challenges in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation and Management” and presented “Impact of Snake Fungal Disease on Population Viability” at the 78th Midwest Fish and Wildlife Conference in Milwaukee, WI. Jan 28-31.

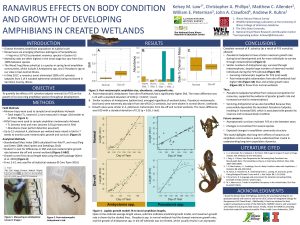

Student Kelsey Low presented a poster on “Ranavirus Effects on Body Condition and Growth of Developing Amphibians in Created Wetlands”